Welcome Home

America’s involvement in Southeast Asia began shortly after World War II. In the beginning, the United States sent only money and military advisors to assist South Vietnam in their fight against the communist forces of North Vietnam. A decade later, U.S. assistance also included elite combat troops to further bolster South Vietnam’s military effort. America’s involvement in Vietnam would continue to escalate for another decade even as public support for the war began to decline.

The Orange Heart Memorial in Springfield, Tennessee, USA.

The Orange Heart Memorial in Springfield, Tennessee, USA.

By 1970, U.S. presence in Vietnam stretched across 25 years and the American public was growing tired, angry, and increasingly divided. Unlike the celebrated and well-respected WWII heroes returning from the beaches of Normandy or the Battle of the Bulge, American soldiers coming home from the jungles of Vietnam were often regarded as pariahs, baby-killers, and drug addicts. There were no parades to welcome the Vietnam veterans home. Instead, many Americans took to the streets to protest our continued involvement in the war.

Against this angry backdrop, however, a small bright spot emerged. Calls to “Support the Troops, Not the War,” began to be heard. In California, a student-led group called Voices in Vital America, began making bracelets engraved with the names of American prisoners of war (POWs). Millions of bracelets were sold and those who wore them pledged to take them off only when the named soldier, or his remains, returned home.

American dissent had an impact and as the world welcomed the start of 1973, the Nixon administration devised a strategy to end U.S. presence in Vietnam. As the U.S. began withdrawing troops, negotiations with North Vietnam ensued to have our POWs released. The negotiations were successful, and Operation Homecoming was launched. In February 1973, the first group of newly released POWs were flown to Clark Air Force Base (AFB) in the Philippines for medical care prior to the long trip back to the United States.

When the first group of POWs arrived at Clark AFB some of the men had an unexpected request. Having been separated from their own children while in captivity, they asked to leave the hospital to visit the local schools. The visit was a huge success, and similar events quickly became a Clark AFB tradition. A month after the first group of POWs landed at Clark, Lieutenant Commander Dave Carey was released from captivity. It was March of 1973 and Wagner Middle School’s turn to host the POWs.

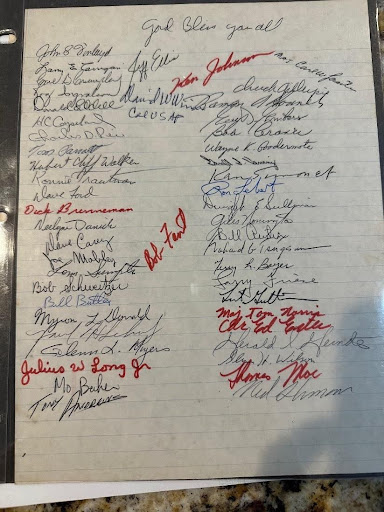

Ricky Ward, whose father was an airman stationed at Clark AFB, attended Wagner Middle School. As he and his fellow students awaited LTCD Carey and the other POWs, Ricky had an idea. When the commander had finished speaking with the students, the young middle schooler handed him half a dozen sheets of notebook paper. Ricky asked the naval aviator to have all the POWs sign them. LTCD Carey agreed and soon returned three sets of signatures to his young admirer.

Meeting Carey and the other men—all heroes in Ricky’s mind—would play a pivotal role in his decision to join the Army Airborne and serve in Desert Storm. Little Ricky grew up to be a big man and the men he served with soon nicknamed him Tank.

Eventually, Tank would gift one set of POW signatures to the Smithsonian Museum and a second to the Vietnam War Museum. The final set he cherished and kept for himself until late in his life. When Tank realized he would leave this world without heirs, he gave remaining signature pages to a friend and fellow soldier.

Paula Austin, the now retired Marine Corps veteran with whom Tank entrusted the cherished pages, recently gave them to me—not a soldier but a grateful American who understands their significance. Of the 660 POWs who survived the war, 110 landed at Clark AFB on March 14, 1973. Fifty-one of those men signed Ricky’s pages.

Jerry Gerndt wearing the multiple POW remembrance bracelets sent to him after he returned home. He was one of the signers of Ricky's papers.

Jerry Gerndt wearing the multiple POW remembrance bracelets sent to him after he returned home. He was one of the signers of Ricky's papers.

The release of the American POWs was an important turning point for a deeply divided nation and marked the first step in the long road to healing. Another major step forward in that process was the establishment of the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington DC. The sleek, black granite structure, known simply as “The Wall,” was completed in 1982 and is inscribed with the names of the 58,318 soldiers who died during the war.

In Springfield, Tennessee, far from the nation’s capital, another Vietnam Veteran Memorial can be found. Unlike the Wall, the Orange Heart Memorial is inscribed with the names of those who survived the war and returned home to a nation who seemed not to care.

April 1975 will mark the 50th anniversary of the fall of Saigon; yet the passage of time has done little to erase the emotional and physical scars left by the Vietnam War. The Orange Heart Memorial was created as another step toward healing and this monument will soon include the names of the men who inspired young Ricky so long ago. Although the pages from Ricky’s notebook will eventually turn to dust, the Orange Heart Memorial will remain. It stands as a permanent “Welcome Home” to the soldiers who answered the call of our nation and ensures they will never be forgotten.

One of notebook pages signed by POWs in 1973.

One of notebook pages signed by POWs in 1973.

Quick Links

| Pages | Other Pages | |

|---|---|---|

| Home | The Agent Orange Trilogy | |

| The RAM Blogs | Edge of Justice | |

| Books | Help | |

| Media | ||

| About Me | ||