Uncharted Territory

Kevin in high school, circa 1969.

Kevin in high school, circa 1969.

“I will not follow where the path may lead, but I will go where there is no path, and I will leave a trail.” -from Muriel Strode’s 1903 poem “Wind-Wafted Wild Flowers”

When my sons were very young, they loved a TV cartoon called Phineas and Ferb. It was a show about two young boys and Perry, their pet platypus. Perry, who was actually an undercover agent, frequently disappeared to battle Dr. Doofenshmirtz who wanted to destroy humanity. It was a crazy and fun 30-minute adventure for my sons, but for me it was yet another cartoon with a bumbling and evil scientist. Contrary to the many scientific villains that Hollywood serves up, most real-life scientists are trying to do good. For most, the goal is understanding. For it is only by understanding something that there is a possibility to repair what is broken. This is the story of one scientist and his journey to make a difference.

The hero of this not-so-epic tale is Kevin Gene Osteen. The second of three sons, Kevin was born in North Carolina in the shadow of the Appalachian Mountains shortly after the end of the Second World War. His mother, the daughter of a moonshiner, was made an orphan after he was killed. He was a man caught doing the wrong thing for the right reasons—and it cost him his life.

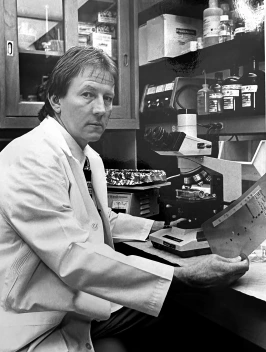

Dr. Kevin Osteen in his laboratory

Dr. Kevin Osteen in his laboratory

at Vanderbilt University Medical Center

about 1993.

Eugenia eventually married but came to suffer from severe agoraphobia. Her fear of leaving home, combined with a husband who worked far away, led her middle son to become quite protective of her. A few miles from their home stood the Craggy Correctional Center, a medium security prison which regularly experienced escapees. As a youngster, Kevin often found himself standing guard with a shotgun ready to defend his mother if needed.

Kevin thrived outside in the Carolina mountains, and his natural athleticism allowed him to excel in school sports. For a while he thought he had a shot at a career in baseball, but a broken leg sidelined those dreams. After finishing high school, he was bound for college instead of the major leagues.

Less than a year after he finished high school, America held its first Vietnam War lottery draft. Because he was in college, Kevin easily obtained a deferment. Many of his friends, though, were sent to war and more than a few never returned. The deferment didn’t feel right to him, and eventually he chose to accept an A-1 status, meaning he was eligible for the draft. His conscription letter never came, and he finished college without interruption.

After college, Kevin was asked to join a team building the Alaskan pipeline. Although the thought of the Alaskan wilderness appealed to him, Sara Jordan appealed to him even more, and he chose marriage over the call of the wild. Sara, long before she was an award-winning teacher, saw something in Kevin perhaps even he himself didn’t see. She encouraged him to go to graduate school and see where his potential would take him. It was good advice.

Kevin with his wife Sara and daughter Amanda about 1984.

Kevin with his wife Sara and daughter Amanda about 1984.

Forty years ago this month, in July of 1983, Kevin Osteen, PhD, joined the ranks of scientists working at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee, USA. His first order of business was to take the reigns of the fledging in vitro fertilization (IVF) clinical laboratory and make it functional. He was successful, and soon Tennessee’s first certified clinical lab to help infertile couples conceive was open for business.

But, like most scientists, being able to help patients wasn’t Dr. Osteen’s only goal. Instead, he wanted to discover the root cause of their infertility in an effort to prevent it. In other words, although he helped establish one of the first IVF clinics in the U.S., his ultimate goal was to make such clinics obsolete. His studies focused on the human ovary since this tissue produces the egg that, following fertilization by a human sperm, creates an embryo with the potential to grow into an entirely new person.

Late one evening, Kevin was alone working while Brandenburg’s concerto boomed loudly across his laboratory. Fred Gorstein, MD, happened to be walking by and stuck his head in to listen. The two began to talk and soon a collaboration was born. Kevin would help Fred examine the endometrium. Since the endometrium is where the embryo implants and grows, it is just as important as the ovary for a healthy pregnancy. It made sense to study both.

Fred soon introduced Kevin to Lynn Matrisian, PhD. Unlike Kevin and Fred, she wasn’t interested in reproduction; she studied cancer. Since embryo implantation is an invasive event, Kevin wondered if the process would use the same enzymes that a cancer used to invade and spread. Could studying cancer improve human fertility? Asking that question unexpectedly led the group to stumble headfirst into a disease called endometriosis. It is a painful and debilitating disease of reproductive-age women and is often associated with infertility.

Just as Kevin’s team was developing a strategy to study endometriosis, I decided to pursue a PhD degree. I joined Kevin’s laboratory and soon found myself walking beside him on the road less traveled. Together, we have expanded our studies to include male reproduction, offspring health, and toxicology. Our group was the first to demonstrate that paternal exposure to dioxin, the toxic chemical found in Agent Orange*, led to adverse health effects in offspring. Although this was new information to the scientific community, it came as no surprise to veterans of the Vietnam War.

I tell Kevin’s story because Hollywood won’t. He has been recognized with numerous awards for his work, but, even so, his 40-year career is unlikely to be considered “big screen” material. Although he never had to defend his mother against a prison escapee, he has conducted groundbreaking research to improve the health and lives of all women. He wasn’t asked to fight in Vietnam, but now he fights on behalf of Vietnam veterans everywhere.

Kevin’s journey won’t entertain children on a Saturday morning, but it’s still a story that deserves to be told. It is a story of perseverance and determination and of forging a path where there wasn’t one before. He may not be able to leap over buildings in a single bound, but the scientific leaps he has made are both impressive and far-reaching. Perhaps by the time he decides to hang up his lab coat, Hollywood will be ready for a new kind of hero.

*Agent Orange was an herbicide used extensively during the war in Vietnam and has been linked to a wide range of adverse health effects in both Vietnam veterans and the Vietnamese population. More detailed information on Agent Orange can be found at: Unintended Consequences: The Agent Orange Story

March 2023

Quick Links

| Pages | Other Pages | |

|---|---|---|

| Home | The Agent Orange Trilogy | |

| The RAM Blogs | Edge of Justice | |

| Books | Help | |

| Media | ||

| About Me | ||