Thursday’s Child

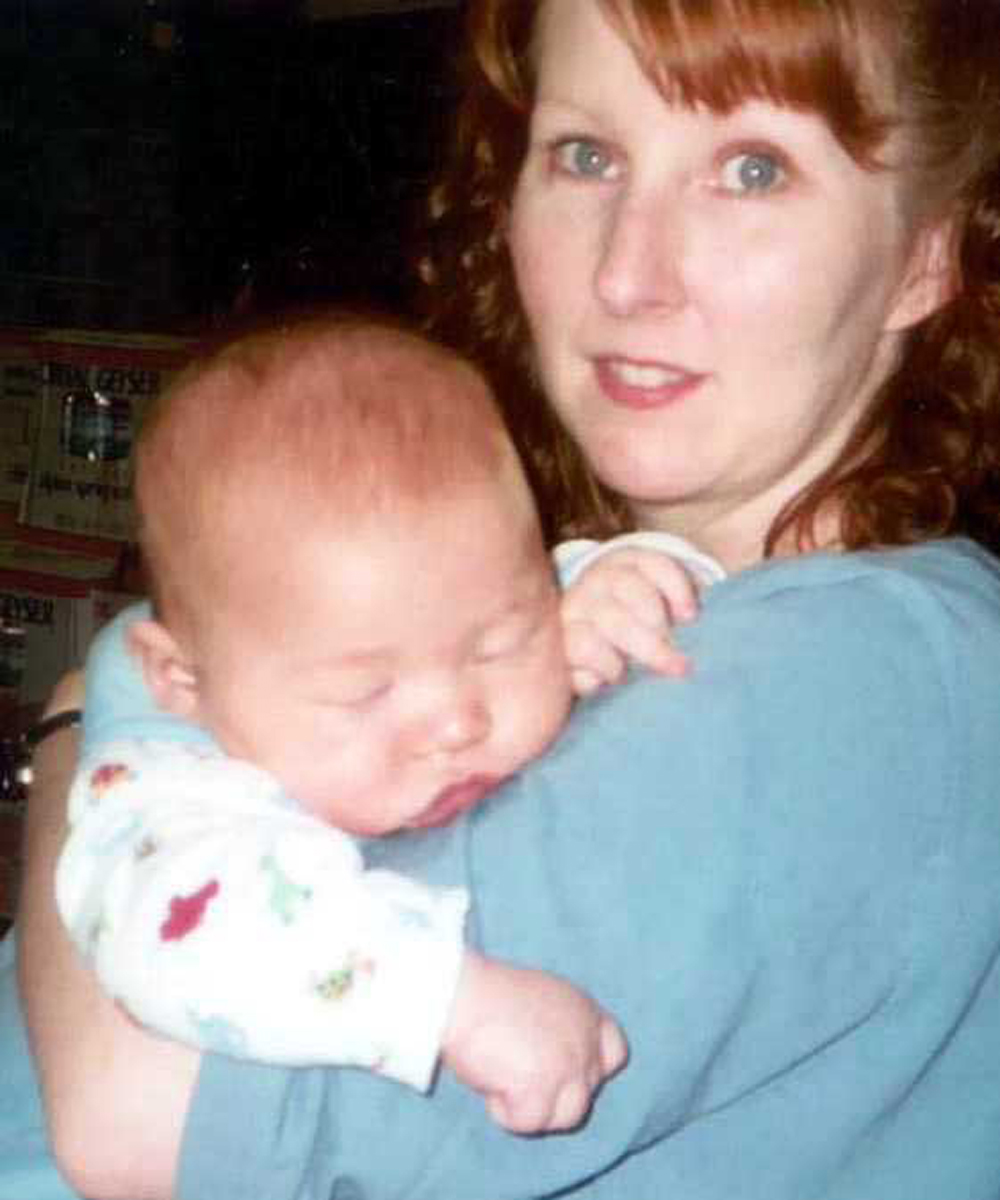

Kendrick, age 3 months, with mom Kaylon in 2001.

Kendrick, age 3 months, with mom Kaylon in 2001.

When my first child was born at 5:24 A.M. on September 20, 2001, he just missed being “Thursday’s Child.” As a human-interest story, a Nashville TV station ran a news feature profiling the family of the first baby born each Thursday. At first, I was a little disappointed. Kendrick was perfect, and I wanted to show him off. It turns out that the baby born first, who was also a boy, was born at just 27 weeks. Normal gestation for humans is 40 weeks. As I held my son in my arms, the story I saw on TV that night showed a tiny, red-faced infant in an incubator. I know nothing more of that little boy or his family. Over the years as I watched my son grow, I have often thought of that child. Did he survive? Is he strong and healthy like my son or does he suffer because he was born too soon? I will never know, but I will never forget him.

In addition to being a mom, I am a scientist and have spent my professional life studying reproductive diseases. In 2001, when Kendrick was born, we had just established the developmental dioxin exposure model that we now use extensively to understand the effects of that common toxicant. The model was originally designed to aid in our studies examining the causes of endometriosis, a reproductive disease that some women develop. The model was a success, and the toxicant-exposed female mice had numerous features that resembled women with that disease. Since women with endometriosis are often infertile, it seemed appropriate to mate our mice to see if their fertility was also compromised. At that time, I had never mated mice and was only certain an animal was pregnant when she began gaining weight. A week or so after mating, all the control mice were gaining weight, while only half of the toxicant-exposed mice looked like they might be pregnant. Gestation in a mouse is only 20 days; however, these first pregnancies weren’t timed and so I wasn’t sure when the pups would be born (again, I was only interested in fertility back then). Consequently, it seemed prudent to check on the mice

each day until the pups were born.

Finally the day came when I went to the animal facility and found pups. At first, I was excited. However, the pups were very small and very red. Something seemed wrong, but I didn’t know what. The unexposed mice were still pregnant. It was only the dioxin-exposed mice that had delivered. I looked at the picture chart on the wall of the animal care facility with images of mouse pups, newborn to Day 21. My pups should be pink, not red. They should not be so small. Suddenly the image of “Thursday’s Child” came to me and I knew. I also knew that my research focus had just changed. I had spent 20 years studying endometriosis, but at that moment I knew I would spend the next 20 years researching the causes of prematurity.

Louis Pasteur famously said, “Chance favors the prepared mind.” It was purely happenstance that my son was born the same day as another child who was born too soon. But it was that experience that prepared me to realize that in our effort to create an endometriosis model, we accidentally developed what may be the only mouse model of spontaneous preterm birth. Over the years since then, we have learned much from this model and are optimistic that it will eventually help us prevent preterm birth of human infants. To me, studying this model is not just a research opportunity, it is a responsibility. We have to figure this out for Thursday’s Child and every other child who will be born too soon if we don’t.

Quick Links

| Pages | Other Pages | |

|---|---|---|

| Home | The Agent Orange Trilogy | |

| The RAM Blogs | Edge of Justice | |

| Books | Help | |

| Media | ||

| About Me | ||